The worlds we see on screen do not build themselves. Behind every chandelier lit ballroom or pink-saturated fantasyland is a pair of hands that are often unseen and often uncredited. These are the teams making decisions about who matters, what power looks like and how the story gets told by two women in set design that are crafting something for the next generation.

“Film can feel like it’s on a pedestal. But it starts at a table just like this.” — Sarah Greenwood

For Academy Award–nominated production designers Sarah Greenwood and Katie Spencer, their work is not just about creating beauty. It’s about shaping perspective. It’s about reclaiming narrative space for women in film. And more than anything, it’s about inviting the next generation of women in to this world.

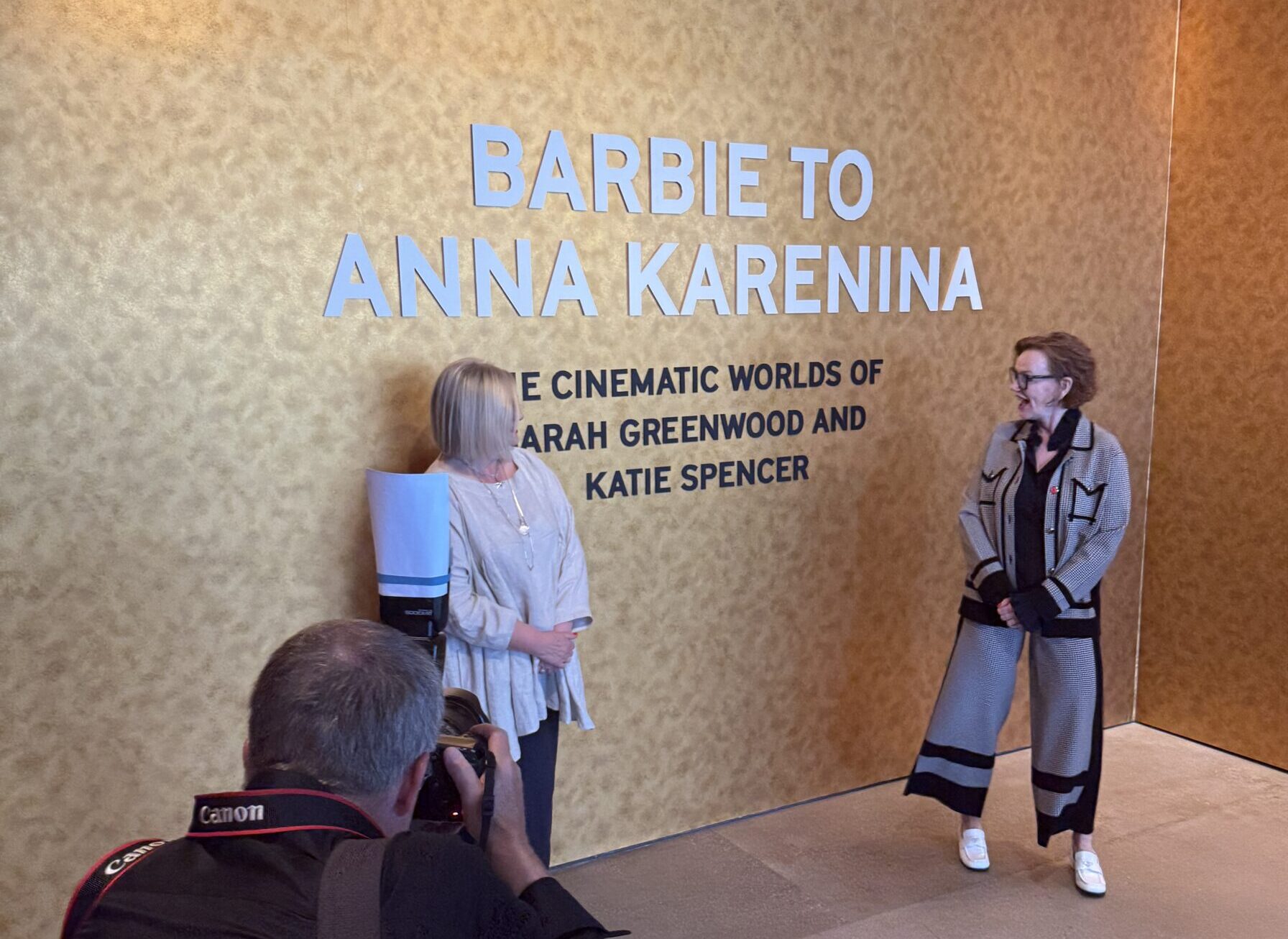

I sat down with the duo at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, inside the exhibition Barbie to Anna Karenina. What unfolded wasn’t just an interview about design. This was a conversation about empowerment, visibility and building a creative industry that doesn’t shut young people out.

Set design is not just decoration.

It is authorship.

“These are all female centered stories. All of them. A female sort of journey through,” said Katie Spencer. “Anna Karenina. Barbie. Beauty and the Beast.”

That is not a casual observation. It is a statement of purpose.

Sarah Greenwood and Katie Spencer do not just dress the set. They construct a framework for the story. A visual language that holds space for women to exist, resist and unravel. And in this exhibit, their work is not background. It is the narrative.

Each set reveals how a woman navigates a world built to confine her. In Anna Karenina, Greenwood and Spencer turned spaces into systems of control. In Beauty and the Beast, they helped reinterpret a fairytale through a feminist lens. In Barbie, they pulled from Ruth Handler’s original vision and transformed a childhood icon into a statement of possibility. This is the power of women in set design.

“I had to readdress how I felt about Barbie after getting into it,” Katie said. “The whole story and the making of Barbie and Ruth’s story and why she made Barbie when she just made the dolls really for her children… it became quite a female centered exhibition.”

The work is intentional. Every detail pushes back on what we have been told to accept.

That work is now being seen on its own terms.

“We are not often the center of an exhibition,” Katie said. “But we should be.”

This moment is not just about visibility. It is about authorship. Greenwood and Spencer are not illustrating someone else’s version of the story. They are telling it. In color. In silence. In space. And they are doing it with power.

“These are all female-centered stories… Anna Karenina, an amazing book, a woman who tried to break the system” – Katie Spencer, highlighting the importance of preserving complex women’s narratives

This exhibit invites girls into the conversation

Set design is one of the most powerful forms of storytelling in film, but it is rarely presented as a career path, especially to young women. It is easy to love movies without being told who builds the worlds inside them. That silence is by design of old Hollywood institutional beliefs and systems, and this exhibition breaks it. Greenwood and Spencer made sure that what visitors see is not just the polished result but the full creative process.

Their actual studio space has been recreated inside the museum, filled with sketches, swatches, notes, easter eggs and the kind of visual chaos that makes ideas real. It is not a pristine showcase. It is a working space that remains honest, human and full of possibility.

“I never knew even my job existed until I was in my twenties,” Katie said. “That is why we showed our office space. To demystify it.”

There is also a hands-on design station where future set designers and young creatives can play, build and experiment. It is not just a feature of the exhibit but it send this message. You can do this too and not just someday, if you wish hard enough, but right now because women are part of the story.

“Hopefully this will show that it is possible,” Katie said. “Whoever has the tenacity or the talent to come in.”

That is what real access looks like. It is not filtered or carefully curated to look untouchable. It is messy, creative and open. By showing the real workspace and by letting kids build their own sets, this exhibit does more than educate. It invites. It plants the idea that women and girls are not just welcome in these rooms. They are needed here.

“Women excel at storytelling visually,” Katie said. Sarah nodded and added, “They really do.”

This is not about who gets to be included. It is about who has always had the talent, the eye and the imagination and who finally gets to see themselves reflected in the process.

“If you look at the way the sets for the Karenina house were made, you can see how oppressive [her world] is” – Sarah Greenwood, demonstrating how design can provide deeper narrative context

Design as power, beauty as strategy

During our conversation, I asked something that has stuck with me for years. As designers who build entire visual worlds around women’s stories, do they see beauty as a strength or a liability? In an industry that often equates femininity with softness or decoration, what does it mean to design with intention and power? For Greenwood and Spencer, beauty is never added for effect. It emerges from the narrative itself.

Sarah answered first.

“We do not isolate those kinds of things for specific reasons,” she said. “If it comes out of the story, we use it. We search for truthfulness in what we do.”

Their designs do not just support the story. They reveal it. And sometimes, they challenge the viewer to see it differently.

Katie Spencer noted that Beauty and the Beast was a particularly meaningful project, with Emma Watson pushing to shape Belle into a more feminist character. That shift allowed the team to design a world that supported a stronger, more intentional version of the classic heroine.

“Beauty and the Beast was fascinating,” Katie said, “especially with Emma Watson trying to make Belle a more feminist character.”

Another perfect example is the Mojo Dojo Casa House from Barbie. Greta Gerwig asked them to make it ugly. So they leaned in and created something loud, excessive and painfully familiar. With La-Z-Boys, mink coats and shelves of protein powder, it became a visual critique of performative masculinity. Every piece in that room had something to say.

“If it is in the storytelling, we lean in,” Sarah said. “Women’s stories deserve the full spectrum.”

Their work is not passive. It does not sit quietly in the background. It challenges, sharpens, and reframes. They are not designing for the male gaze. They are designing to show what the gaze has overlooked.

“Quite often the mother is portrayed as some sort of idiot woman. But this is a woman who was desperate – if the husband died and she hadn’t married off those girls, then they were destitute” – Katie Spencer, showing how design and staging can recontextualize characters’ motivations

Why this matters now

Hollywood is at a crossroads. Conversations around inclusion are being diluted. Diversity efforts are being quietly rolled back. Young people are told to be patient. To wait. To earn their way into rooms that were never built with them in mind.

This exhibition answers that with something louder than just women in set design.

It says you do not have to wait. You can start now. You can shape this world if you are ready to speak through design, through color and through space.

“Be energetic. Be curious. Know your subject or go find it,” Sarah said.

And most importantly, do not be intimidated by the scale of the industry. Every massive production begins with a question on a piece of paper or a vision scribbled in a notebook.

“It starts at the baseline,” Sarah added. “Then it grows. And it grows.”

On their collaborative approach, Katie Spencer noted they are “lucky to have worked with directors, both men and women who want to go outside of that norm, to show a different side of women.”

Beyond being just “women in set design” they have a shared commitment to breaking traditional narrative boundaries and it defines their work. It is not just about visual storytelling. It is about reclaiming history, challenging assumptions, and making space where women have always belonged, even when the story never said their name.

“Anna Karenina was ahead of its time when Tolstoy wrote it, ahead of time when Tom Stoppard adapted it, and ahead of time when we made it” – Sarah Greenwood

Final thoughts: This is their story.

And they are telling it in full color.

Sarah Greenwood and Katie Spencer are not just designing sets. They are designing possibility.

Through their work, they have created spaces where women are fully realized and where history is told through a lens that honors complexity. This is where young people can see their future not as a distant hope but as a present opportunity.

Their sets do more than support a story, they question it. They challenge the audience to look closer and ask who built this world and who was left out of it.

This exhibit is not about nostalgia. It is about evolution. It is about what happens when women are trusted to shape the frame, not just as decorators or support staff, but as authors in their own right.

“We search for truthfulness in what we do,” Sarah said.

They have done exactly that, not from the sidelines but with boldness, clarity and a creative vision rooted in beauty, intellect, and skill.

“We want to show that it starts at the baseline,” Sarah added. “Don’t be intimidated and try and get on that train of opportunity.”

This is not just a career. It is a calling that honors the Academy’s mission to preserve and promote cinematic artistry. And now that it is visible and women in set design are being honored, there is no going back.

To experience the extraordinary visual worlds of Barbie to Anna Karenina: The Cinematic Worlds of Sarah Greenwood and Katie Spencer, head to the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. This immersive exhibition, curated by Michelle Puetz, offers a rare look at the artistry behind some of cinema’s most iconic sets. Get your tickets now at academymuseum.org/tickets

Leave a Reply