Let’s not sugarcoat that Griffith Park is one of the most beloved spots in Los Angeles, but the man behind it, Griffith J. Griffith (so nice they named him twice) was chaotic as hell.

He had a ridiculous name, a drinking problem he swore he didn’t have and a full-blown conspiracy theory that the Pope was trying to poison him through his wife. He shot that wife in the face in a Santa Monica hotel room, went to prison, came out swinging with a redemption arc no one asked for and somehow still got a telescope and a Greek Theatre named after him.

But before we talk about Griffith J. Griffith, the loaded pistol and the legacy makeover, we need to talk about the land itself and how his story only exists because of what was taken first.

Before It Was a Park, It Was Stolen Tongva Land

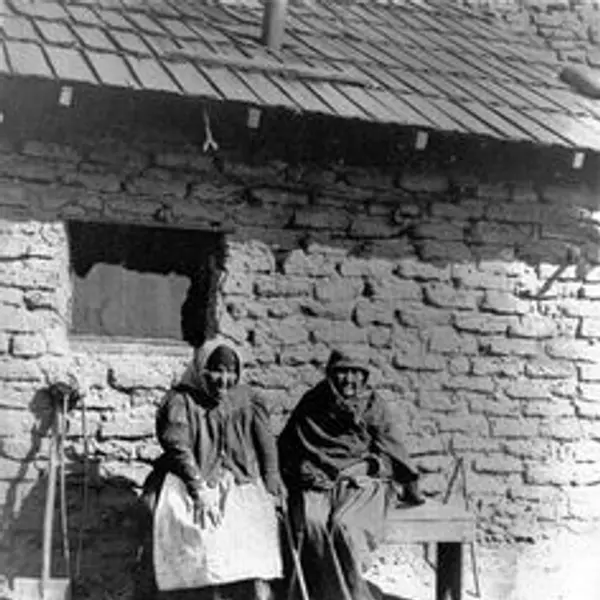

Long before Griffith ever set foot in California, this land belonged to the Tongva people and not in some abstract, symbolic way. There were thriving Tongva villages within what we now call Griffith Park. One was near Fern Dell, another sat west of Travel Town near today’s Universal City and a third was where the old Feliz adobe and current ranger station still stand.

Again, this was Indigenous land where Indigenous people lives and Indigenous communities were doing just fine without outside assistance.

This land held life and held ceremony, community, history and meaning. It was never empty. It was never up for grabs. And yet, like so much of Los Angeles, it was carved up, claimed and renamed.

After Spanish colonization, the land was handed over to José Vicente Feliz through a land grant in the late 1700s. He called it Rancho Los Feliz. After Mexican independence, the land remained in the family. Doña María Ygnacia Verdugo secured water rights and passed the rancho to her daughters, who sold it off for a dollar an acre while her son, Antonio, held the rest.

When he died, people started whispering about the “Curse of the Felizes,” but the real curse was settler greed.

Also, quick note for the pronunciation police. Locals call it “Los FEE-lis,” but the proper Spanish is “Los FEH-lees” and we feel like that’s important because it’s a controversy in Los Angeles.

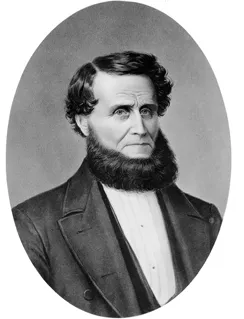

Who Was Griffith J. Griffith?

Griffith Jenkins Griffith came to LA with silver money in his pockets and legacy on his mind. Born in Wales, he made his fortune in Mexican mining and immediately set to work branding himself as a self made visionary. He made people call him “Colonel,” despite having no military service. He signed hotel ledgers like a man expecting a statue and acted like he invented civic virtue.

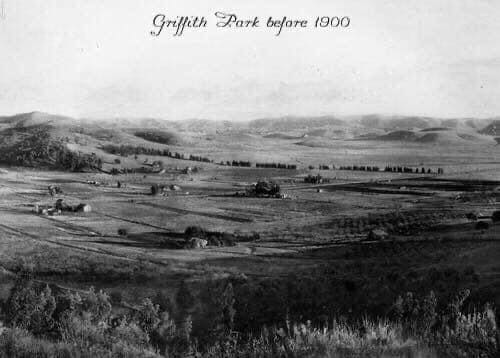

By the 1890s, he had bought a massive chunk of the old Rancho Los Feliz estate. He built a mansion and named the surrounding area “Griffith’s Park” because subtlety wasn’t in his vocabulary. In 1896, he donated 3,015 acres to the city of Los Angeles, even though the land was outside the city limits at the time. He said it was a gift to the people. What he didn’t highlight was that the land came with water rights and that’s what the city really wanted.

The mayor called it a “princely gift,” but it was also a strategic one. It gave Los Angeles control of the land, of resources and eventually, of Griffith’s name, which is now etched into signs, maps and buildings like he was some kind of hero.

Except he wasn’t.

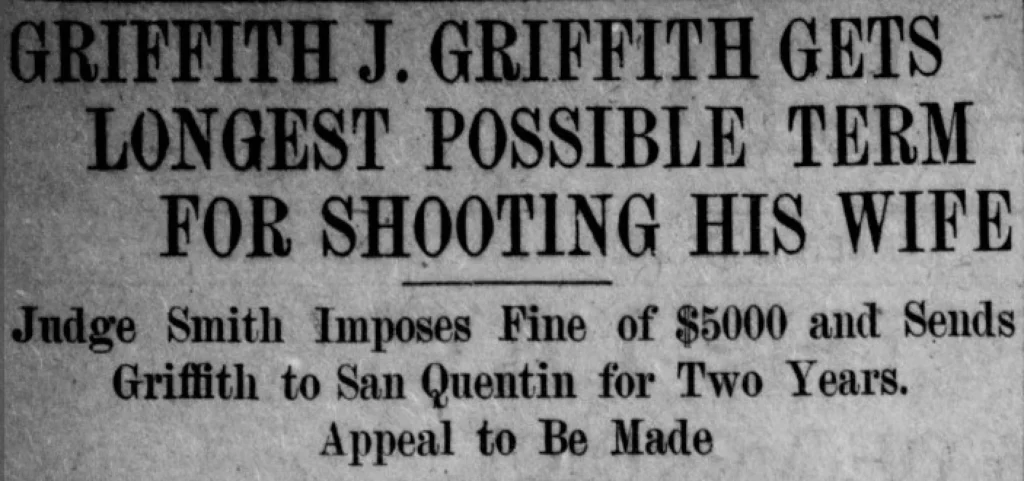

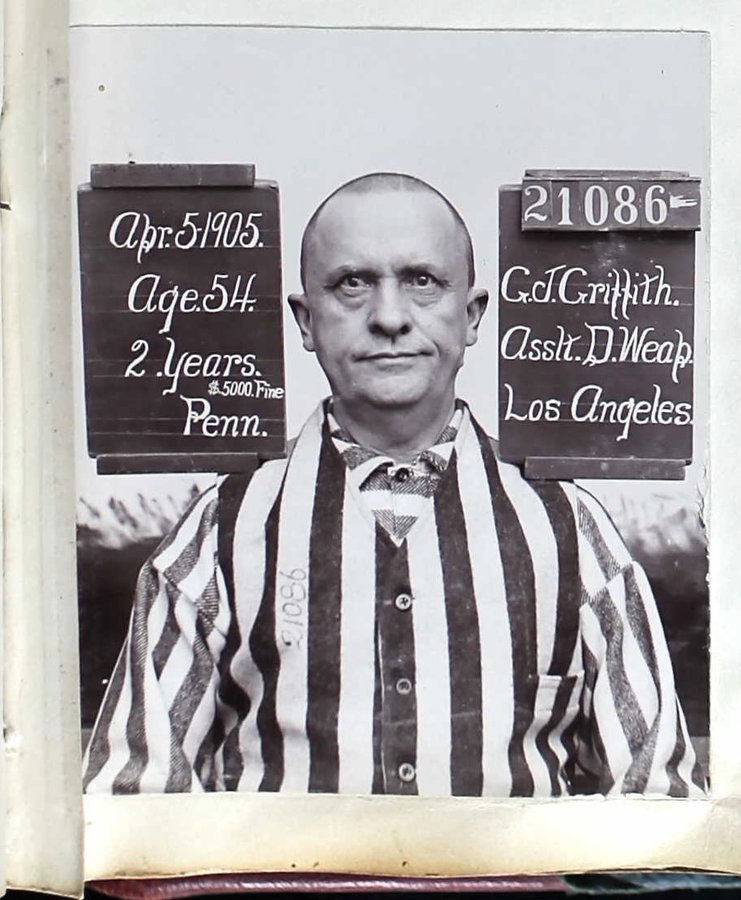

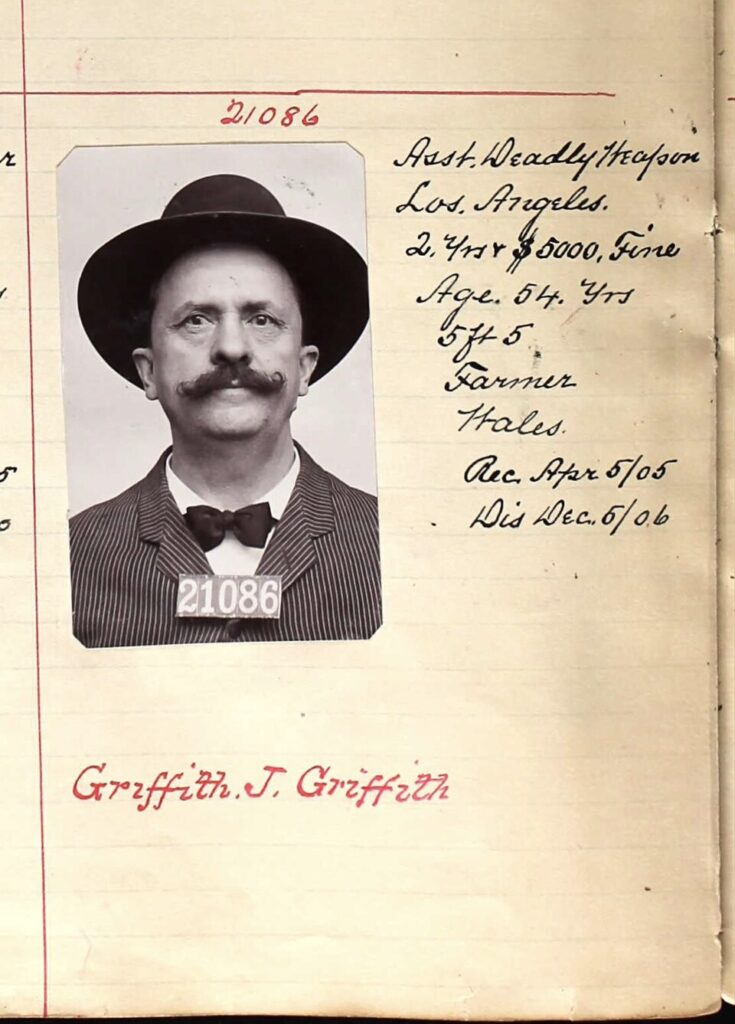

Griffith J. Griffith preached temperance while sneaking whiskey into hotel rooms. He claimed moral authority while accusing his wife of being part of a Catholic plot. He tried to kill her, served two years in San Quentin.

The park still bears his name. The telescope still looks out over the city. The messy, violent, delusional man behind all of this still gets called a philanthropist.

The Santa Monica Shooting: When the Mask Finally Slipped

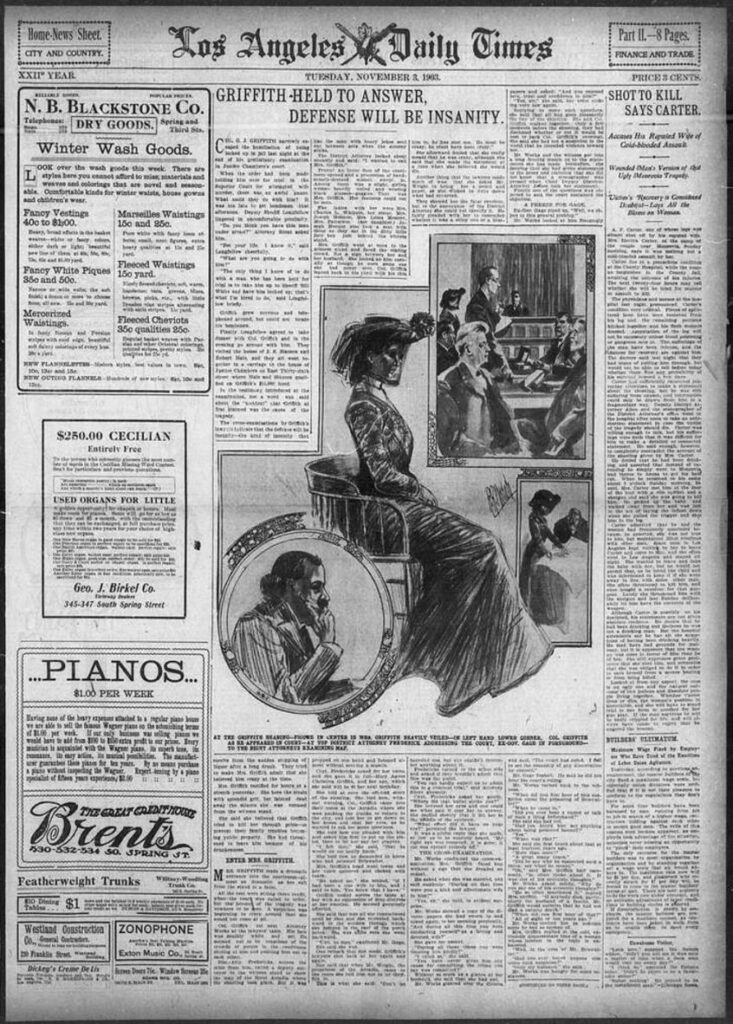

By 1903, Griffith J. Griffith had officially lost the plot. The man who donated land to the city, preached morality and demanded everyone call him “Colonel” was spiraling. His drinking, which he swore he didn’t do, had escalated into binge sessions fueled by religious paranoia. He believed his wife, Tina Mesmer, was conspiring with the Pope to poison him. Because of course she was. She was Catholic and that was all the evidence his whiskey-soaked brain needed.

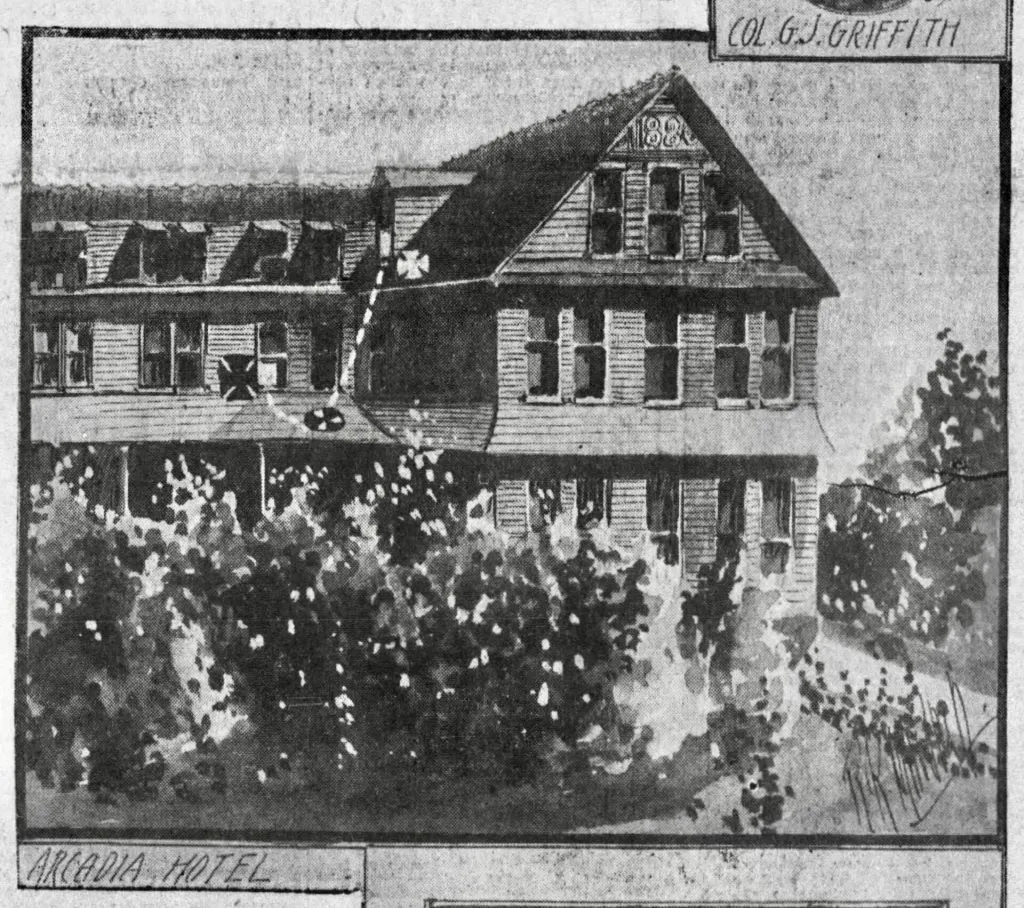

They were staying at the Arcadia Hotel in Santa Monica, a seaside escape the family visited every summer. This wasn’t some spontaneous weekend trip. It was part of their annual routine. They’d been there for about a month with their 15-year-old son, Van, when he finally snapped.

He smuggled a bottle of whiskey and a loaded gun into their suite, waited until Tina was reading a book in bed, then told her to get on her knees and pray. When she refused, he shot her in the face.

Let me say that again. He shot. His wife. In the face.

Somehow, she survived. Tina jumped out of a second-story window and escaped.

She lost her right eye and lived the rest of her life with a glass one, disfigured and traumatized. Griffith was arrested and charged with attempted murder but this was 1903 and white men with money didn’t face justice, they got leniency and a second chance. Yes, I know what you’re thinking: this is totally the way it is now. Same.

Tina files for divorce and gets custody of their teenage son. The jury convicted him of assault with a deadly weapon instead. Not attempted murder. Just a little casual “oops” with a firearm.

He was sent to San Quentin. And somehow, that wasn’t the end of his public life. It was just the beginning of his next act.

What Happened to griffith j. griffith at San Quentin

Griffith J. Griffith walked into San Quentin not as a disgraced man but as a delusional one. He served just under two years for shooting his wife in the face and came out with a new identity. And, yes, I know what you’re thinking is how is this any different than today. It’s not. He came out not as an ex-convict or the dude who shot his wife in the face, but as a reformer. I’m looking at you over there Menendez Brothers.

He didn’t spend his sentence reflecting on what he did to Tina. He spent it watching other inmates and deciding he was now the moral compass of the prison system. He emerged convinced the system was broken. Not because it let men like him off easy but necause it was hard on everyone else.

So naturally, he went on tour.

Griffith joined the Prison Reform League and started giving speeches about moral rehabilitation and solitary confinement. He said prison gave him purpose. He claimed the experience changed him and not one word about his wife. There was not one ounce of accountability. Now it was just vibes, reinvention and the kind of self-importance only old rich men ever seem to fully master.

He did not ask for forgiveness. He asked for funding. He pitched the city of Los Angeles a plan to build an open-air amphitheater and a public observatory. On that land that he bought from the Spanish and was once home to the Tongva.

It was classic Griffith Jenkins Griffith, a man so wrapped in his own narrative that he truly believed a telescope could erase a bullet.

What About Tina?

Tina Mesmer Griffith survived something most people don’t walk away from, even today. Her husband shot her in the face at point-blank range and left her bleeding in a hotel suite while their teenage son was nearby.

She had to live with the silence of what happened because while Griffith was busy giving speeches and making legacy plays, Tina was just expected to disappear.

No apology.

No restitution.

No justice.

She got a disfigured face and a front-row seat to the world pretending like none of it ever happened.

Luckily for victims and survivors everywhere, she didn’t disappear. Tina filed for divorce as soon as Griffith was convicted. She fought him in court. She testified. She stood up and told the world what he did, even though that world barely listened. While she never got the justice she deserved, she never let him back into her life.

There are no statues of Tina. No plaques. No glass eye in a museum display and you can’t even really find pictures of her.

Every time someone calls Griffith Park a gift to the city, they’re forgetting the woman who paid for that legacy with her body. She was more than a footnote. She was the warning sign and Los Angeles ignored her.

The Observatory, the Ego

and the Pitch That Made No Sense

After getting out of San Quentin and skipping over any form of public accountability, Griffith J. Griffith got back to work. And by work, I mean he decided Los Angeles still needed him and his money. Let’s be very honest that Los Angeles has never been known to turn down any money for anything.

Griffith wanted to return to public life and he wanted to leave behind a monument to himself.

Unlike dudes with statues and memorials, he pitched a telescope because of course he did.

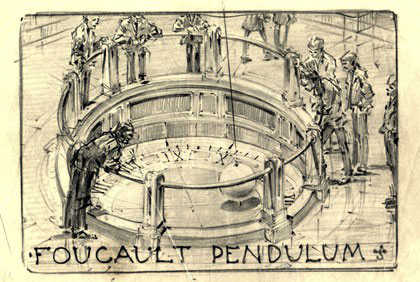

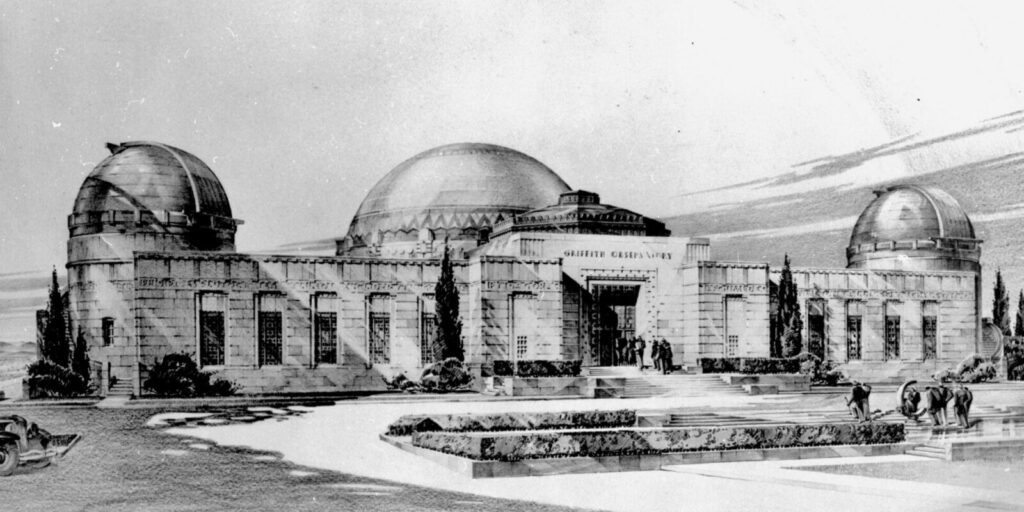

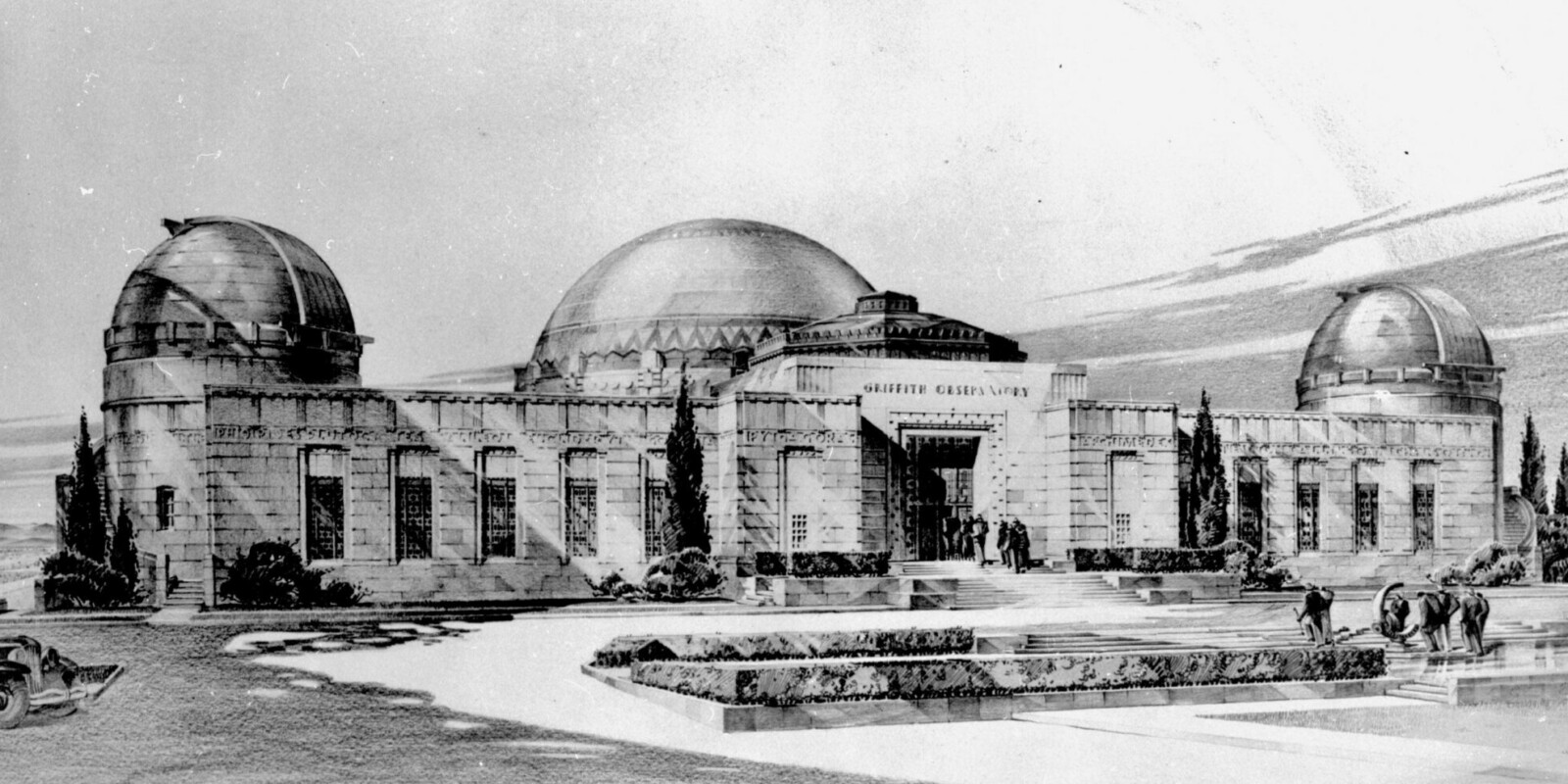

Griffith proposed building a public observatory and an open-air amphitheater on the land he had donated. He claimed it would make science and culture accessible to everyone. He said the stars belonged to the people and that LA needed art and astronomy and he could provide both.

All of this sounds noble now. We love the Griffith Observatory. It’s iconic but in 1905, this was strange behavior. Space exploration wasn’t on anyone’s mind yet. There was no NASA, no Carl Sagan whispering about stardust or making up conspiracy theories about the moon landing.

The average Angeleno was more worried about plumbing and polio than looking at Mars. The idea of building a telescope for the people came off less like civic vision and more like a man trying way too hard to be remembered for something other than shooting his wife.

The city said no. They stalled. They avoided his name. They politely refused to let a man fresh out of prison build anything else.

But Griffith had a backup plan. He left money in his will to fund both the observatory and the theater. So, when he died in 1919, the city shrigged, obviously took the money and moved forward.

By 1935, the Griffith Observatory opened to the public. The Greek Theatre followed. Both were built with his estate and both carried his name.

Everything quietly left out the part where their namesake was an unrepentant, violent man who thought a telescope could wipe his slate clean.

Why We Still Need to Talk About Griffith Today

Griffith J. Griffith isn’t just a historical footnote. He’s a perfect example of how Los Angeles has always had a weird relationship with power, redemption and who gets to be remembered as “visionary” instead of “violent.” The man shot his wife in the face, served less time than most people do for tax fraud, then got his name permanently etched into some of the most beloved landmarks in Los Angeles.

Let’s be clear that people still take engagement photos under the “Griffith Observatory” sign like it was built by an angel in suspenders.

This isn’t about canceling the past. It’s about acknowledging the full story. Griffith gifted 3,015-acre land to the City of Los Angeles on December 1896. That’s true. He also created a redemption narrative for himself at the expense of a woman who lived the rest of her life disfigured and silenced.

Let’s take a moment and remember that Los Angeles was built on contradictions. It’s always been a city of second chances, reinvention and selective memory. Griffith J. Griffith was all three of those things, rolled into one sharply dressed, whiskey-fueled fever dream of a man.

So the next time you hike to the top, stare out over the city and take in that iconic skyline, remember this: you’re standing in a park shaped by stolen Indigenous land, funded by a white man profiting from Mexican silver and named after an abuser who shot his wife and called it legacy.

He thought a telescope could rewrite the story.

And the City of Los Angeles let him.

Leave a Reply