Sixty-five years ago, a screaming Janet Leigh met her end in a flurry of chocolate syrup and razor-sharp edits that changed horror forever. The shower scene in Psycho is still one of the most dissected moments in cinema history and of course it’s always credited to Hitchcock’s twisted genius. But there’s one name that rarely gets mentioned, even though she shaped nearly everything about his process: Alma Reville.

Alma wasn’t just Hitchcock’s wife. She was his closest collaborator. She was in the editing room. She rewrote scripts. She had an eye for continuity, rhythm and story structure. And when Hitchcock put up his own money to finance Psycho, Alma was by his side making sure it worked because, at that point, she had a vested interest in its success..

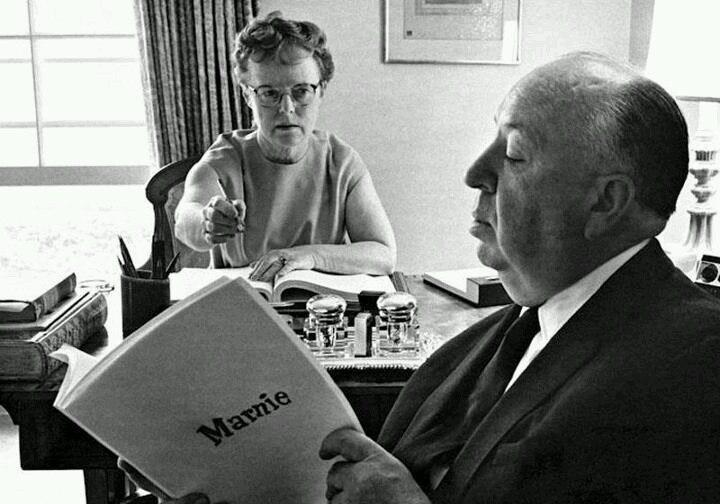

Alma Reville: The Woman in the Room

Before she was Mrs. Hitchcock, Alma Reville was already a powerhouse.

She started in the film industry as a teenager, working as a cutter and script supervisor in the silent era, a time when women were actually more prominent in editing roles. She worked at Gainsborough Pictures and later moved to Famous Players-Lasky, climbing her way up through skill, not nepotism. That’s how she met Alfred Hitchcock. They were colleagues before they were a couple. She had a career of her own, one she built from the ground up.

In an industry that rarely allowed women to lead behind the camera, Alma was already doing it. She brought that experience and precision to every project she touched, including her husband’s. She didn’t ride his coattails. If anything, she helped sew the damn lining.

The Scene That Slashed Its Way Into Film History

“I stopped taking showers and I only take baths.And when I’m someplace where I can only take a shower, I make sure the doors and windows of the house are locked. I also leave the bathroom door open and shower curtain open. I’m always facing the door, watching, no matter where the shower head is.” – Janet Leigh on the filming of the infamous shower scene in Psycho

The brilliance of Psycho’s shower scene isn’t in what it shows. It’s in what it suggests. You never actually see the knife pierce skin. You don’t need to.

Through 78 lightning-fast edits in just 45 seconds the scene weaponized implication and sound, letting your imagination do the screaming.

Bernard Herrmann’s screeching violins get all the press, but the editing is what slices it into your memory.

This sequence became the blueprint for how to kill a woman onscreen without showing the gore. It changed the way violence, sex and suspense were filmed and proved that horror didn’t need monsters when it had suggestion and rhythm.

Just look at Halloween. Carpenter keeps the tension sharp and relentless using long takes, quick stabs of violence and a cold, quiet killer whose knife is just as symbolic as it is deadly. It’s no accident that Jamie Lee Curtis, daughter of Janet Leigh and Tony Curtis (who were still married at the time Psycho was made), became horror’s next scream queen.

Or take Scream. The opening sequence with Drew Barrymore is a direct homage to Psycho. A famous blonde.

A knife. A shocking early death. The fear doesn’t come from what you see. It’s what the camera withholds that keeps you from breathing.

Both films owe their rhythm and restraint to Psycho. And to the people who cut it just right.

The Marriage of ALma reville to alfred hitchcock: Behind the Curtain

Alma Reville and Alfred Hitchcock married in 1926, and from the beginning it was more than just a personal partnership. It was creative. They reviewed scripts together. She sat beside him in the editing room. She even directed second-unit scenes. If there was a Hitchcock film in production, Alma was never far from the frame.

But their marriage was not simple. Hitchcock’s emotional distance, his obsessive control over his actresses and his refusal to give Alma public credit created a complicated dynamic. Still, she stayed. Maybe out of love. Maybe out of commitment to the art. Maybe because she knew the films wouldn’t hold up without her.

Whatever the reason, Alma wasn’t just a wife. She was the studio beside him. And that’s not metaphorical. She physically worked in the same spaces, brought the same level of scrutiny and care and often cleaned up the messes he made, on and off screen.

The Woman and the Obsession

Alma’s brilliance wasn’t just in the editing room. It was in her ability to work alongside a man who was, frankly, obsessed with his leading ladies. Hitchcock’s fixation on actresses like Grace Kelly, Tippi Hedren and Janet Leigh is well-documented.

He controlled their looks, their performances and sometimes their lives. And through all of that, Alma stayed married to him and continued to contribute to his work.

But let’s not pretend it didn’t cost her. While Hitchcock’s obsessions played out on screen and off, Alma Reville kept the machine running. There are stories, albeit quiet ones, that suggest she wasn’t exactly thrilled with his behavior. And how could she be?

She was watching her husband build a legacy off women he fixated on while she cleaned up the cuts, shaped the pacing and got none of the credit.

That’s the real tension behind Psycho. Not just what’s onscreen. But what was happening behind it.

Take the infamous shower scene. Hitchcock subjected Janet Leigh to over a week of filming in a freezing set, under harsh lighting and with little regard for her physical comfort. She endured repeated takes, limited protection and the kind of emotional strain that would never fly on a set today. Alma Reville knew this wasn’t just method. It was obsession. But she also understood the industry she was navigating.

Rather than enabling it, she worked to make sure the end result had purpose. She brought shape and meaning to what could have just been cruelty for spectacle. She couldn’t stop Hitchcock’s obsessions, but she could make damn sure the film said something more than just ‘look at her suffer.’

The Woman Who Saved the Scene

Alma was more than a sounding board. She was a working editor at Gainsborough Pictures before Hitchcock ever directed his first film. She could spot a plot hole from a mile away and she often did, fixing pacing issues, dialogue and structure on scripts that would later win Hitchcock acclaim. When Psycho was being made on a shoestring budget, Alma helped tighten the film in post-production and flagged story issues early.

There are credible accounts of Alma cutting scenes, shaping sequences and even influencing the emotional pacing of Hitchcock’s films. Her sharp instincts helped ground the terror in Psycho and made sure the shock had staying power.

It is said that Alma reportedly caught a moment in the final cut where Janet Leigh could still be seen breathing after her character was supposed to be dead. She flagged it before release and the shot was removed. Her attention to detail saved the scene from breaking the illusion.

Why the Auteur Myth Needs a Rewrite

Let’s be honest. Hollywood loves a solitary male genius. It’s part of the myth machine that keeps the legend tidy and the credit centralized. The story is always more glamorous when one man is framed as the visionary while everyone else fades into the background. But that version erases the truth. Alma wasn’t just part of Hitchcock’s life. She was part of his work.

She read his scripts. She sat in the editing bay. She made the emotional rhythm of his films land harder. She didn’t just support him. Alma collaborated. And in the case of Psycho, where the stakes were high, the budget was low and Hitchcock was betting everything on his instincts, Alma’s contribution wasn’t just helpful. It was the difference between a sharp thriller and a cultural reset. It was essential.

Alma in a Man’s World

The truth is, Psycho was made by men. Directed by a man. Shot by a man. Edited by a man. Scored by a man. From production design to sound, the crew was almost entirely male. With two key exceptions: Peggy Robertson and Alma Reville.

Peggy was Hitchcock’s longtime script supervisor and associate producer. She was the one who found the novel Psycho in the first place and helped shepherd it to the screen. And then there was Alma, cutting scenes, shaping narrative flow and cleaning up what the men left messy.

These weren’t women brought in to take notes. They were women keeping the whole production from unraveling. And they did it in a time when almost no women were allowed to hold that kind of influence in Hollywood.

Alma paved the way for women in film, whether the industry ever acknowledged it or not. Today, editors like Thelma Schoonmaker, Jennifer Lame and Catrin Hedström are shaping modern cinema with the same sharp instincts and narrative muscle that Alma brought to Hitchcock’s world. Directors like Greta Gerwig, Emerald Fennell and Rose Glass are telling stories that once would’ve been dismissed as too messy, too emotional or too female.

Alma didn’t just survive the boys’ club. She helped build a hidden legacy that’s only now being recognized. Her work was the blueprint, others are just finally getting the credit.

Say Her Name

Alma Reville was never supposed to be the star of the show. That’s how Hollywood liked it. Men were out in front and women were behind the curtain. But without Alma, there’s no Psycho as we know it. No flawless pacing. No emotional precision. No legendary shower scene that holds up six decades later.

She worked without applause. She got no Oscar. She wasn’t even credited on some of the films she helped shape. But make no mistake, Alma Reville was not behind the scenes.

She was the scene.

So on the 65th anniversary of Psycho, let’s stop talking about her like a supporting character in her husband’s story. She wasn’t just Mrs. Hitchcock. She was Alma Reville. She was the co-author. The fixer. The finisher. The ghost in the frame.

Say her name because it should have been there all along.

Say it because credit matters.

Say it because the next generation of filmmakers shouldn’t have to dig through footnotes to find the women who made history.

Want to hear how women are still shaping Hollywood from behind the scenes?

Check out our exclusive interview with Oscar-nominated production designers Sarah Greenwood and Katie Spencer, whose work on Barbie, Anna Karenina and beyond shows exactly what happens when women control the visual narrative.

Because from Alma Reville to today’s set queens, the legacy of women shaping cinema is long, powerful and overdue for recognition.

Leave a Reply