By Mi Ran Choi

Celebrated Cellist & Director of Classical Arts, Hollywoodland News

Here’s the church, and there’s the steeple. Open the door(s), and see all the… concertgoers!

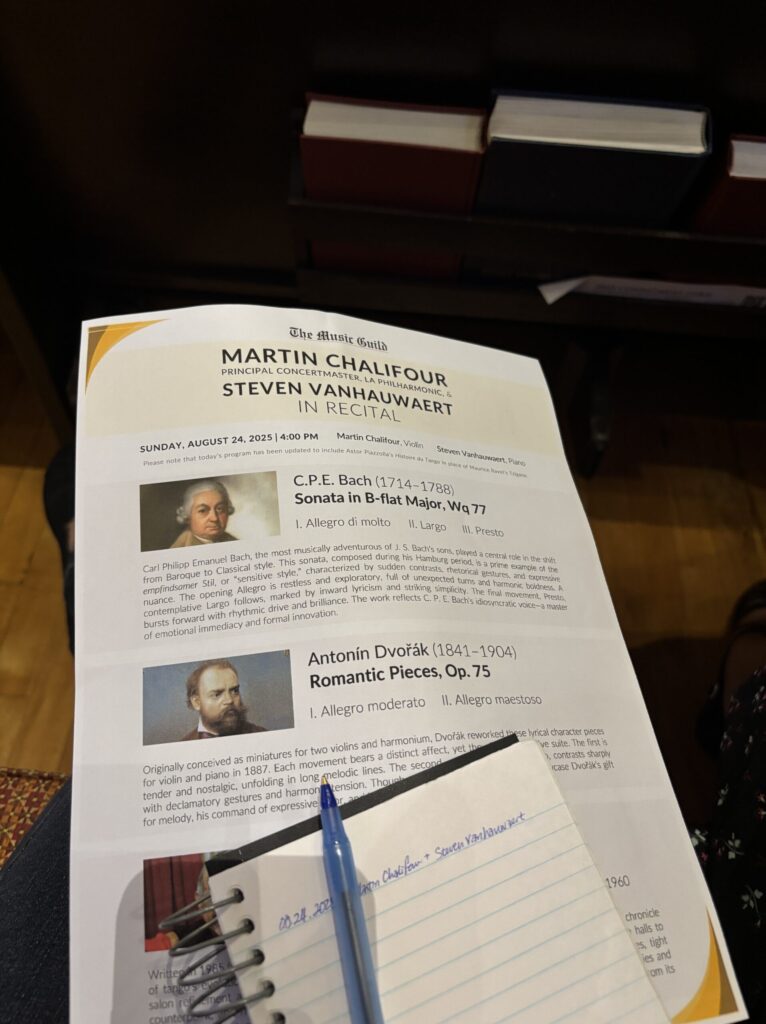

Tucked on a quiet and picturesque hill in Westwood, the stomping grounds of our previously featured composer Sergei Rachmaninoff, chamber music in Westwood at St. Alban’s Episcopal Church bustled with excitement and anticipation long after services concluded that Sunday. Retiring LA Philharmonic Principal Concertmaster Martin Chalifour and world-class pianist and educator Steven Vanhauwaert joined forces to deliver an intimate afternoon of chamber music selections.

The acoustics, the phenomenal spirit through which Chalifour and Vanhauwaert played, the overall amazing vibes… all of it left a pleasant mingling of flavors and aftertaste long after the final piece’s cutoff, as would a finely aged whiskey. What made the occasion all the more special was the rare opportunity to interview both Chalifour and Vanhauwaert after the recital! These interviews will be shared separately from this concert reflection, and I hope our dear readers enjoy these conversations as I did.

But before we dive in, many, MANY thanks to Mr. Sam Varon from The Music Guild for kindly arranging press tickets for Hollywoodland News to cover the recital! For more information on The Music Guild’s work and future events, please keep reading to the end.

Form AND Function:

Where Architecture and Music Meet

Previously, I’ve touched on the overlaps music has with communication, personal and collective identity, pop culture, and social activism. Up next, architecture.

Departing from the deconstructivist intermingling of wood, metal, and glass of the Walt Disney Concert Hall and the Hollywood Bowl’s marriage of nature and solid granite, we have the rich architectural history of Westwood Village. The neighborhood bloomed from the hands of hand-picked architects during the Roaring Twenties and featured a comingling of diversity in styles meticulously arranged to best complement every structure.

St. Alban’s Episcopal Church was beautifully built between 1930–1931 in the Brick Romanesque style (typically found in Central Europe) by architect Percy Parke Lewis. Known for his work on the Fox Theatre and Chateau Colline, also in Westwood, Lewis primarily designed churches, apartment buildings, and theaters, dabbling in in-vogue styles in his time and place, including LA’s ever-present Spanish Colonial Revival style. Vintage cinephiles among you all may have heard of this church already, as this was where the memorial service of esteemed Hollywood director Howard Hawks (1931 Scarface) took place.

Entering the church, I couldn’t help but crane my head around the sanctuary. Both the structure and its inner fixtures (pews, short borders, and tables) were made purely of finished hardwoods, lending the atmosphere a visually warm and cozy vibe as well as a pleasant woody scent.

What I was most concerned with is the quality of the acoustics in the sanctuary, and I suppose “concerned” is the wrong word here. No, I was impressed and entranced by the clarity with which I heard every articulation of every note both Chalifour and Vanhauwaert played — even through the densest of harmonies their pieces employed. It was very clear that Lewis paid painstaking amounts of attention to this detail, which would truly serve the congregation and that afternoon’s music well.

A Violinist and a Pianist Walk Into a Church … for Chamber Music in Westwood

…I don’t have a punchline to complement this subtitle’s start.

Readers of this summer’s music articles may remember Chalifour’s name from our article on our coverage of The Planets at the Hollywood Bowl on July 24th. There, he was featured as the soloist for Ralph Vaughan Williams’ The Lark Ascending in celebration of his contributions to the LA Phil in his extensive tenure as Principal Concertmaster since 1995.

This piece would return on this program, reprised in a much more intimate setting than at the Bowl.

An alumnus of the Curtis Institute of Music, Martin Chalifour has since been recognized for his virtuosic skill at Moscow’s 1986 Tchaikovsky Competition and the 1987 Montreal International Competition and has performed as soloist with many orchestras worldwide.

Championing the 88 keys beside Chalifour was celebrated pianist and Steinway Artist Steven Vanhauwaert. Praised by the LA Times for his “impressive clarity, sense of structure, and monster technique,” Vanhauwaert has performed for radio broadcasts, for concerts with world-class orchestras, for festivals, and for recording studios.

Both musicians hold university faculty positions, are active as masterclass clinicians and festival participants, and are esteemed for their faculties (no pun intended) in repertoire both familiar and new. For a better sense of their discographies, I highly recommend checking whatever streaming platforms you use to see if you can listen to their recordings.

Even just looking at the program for the day, the two musicians’ mettle would be tested in how deftly they would navigate differences in character, timbres, dynamic extremes, tasteful tempi choices… [catching breath] especially considering most pieces were in multiple movements!

The Meat and Potatoes of Chamber Music in Westwood

The music students I’ve taught and coached over the years know me for my near-constant, bordering on absurd analogies, particularly around colors and food. Considering violin and piano works in the ever-growing pool of chamber music literature, I would consider this instrumentation the “Meat and Potatoes” of chamber music instrumentations, as very often, lower string instruments will play arrangements of these pieces. On this note, I fear that my reflections ahead may not be best for those who may be reading on an empty stomach…

CPE Bach: Sonata in B-flat Major, Wq 77

A brilliant appetizer to the multiple-course meal of a recital, CPE Bach’s Sonata was a sampling of a mild stylistic shift away from the cut-and-dry, reserved tendencies of Baroque-era music. Chalifour’s strong, rich tone easily complemented the lyricism with which Vanhauwaert phrased Bach’s relatively sparse harmonies — all without letting go of the levity characteristic of Baroque music.

Though it was the shorter of the two sonatas programmed, boy, was there still a hell of a harmonic exploration to be had and enjoyed. Both violin and piano, or meat and potatoes — I’ll let you decide which is which — navigated the tricky shifts of character between movements and sometimes as frequently as periods (the unit of musical form containing multiple phrases).

Antonín Dvořák: Romantic Pieces, Op. 75

Jumping ahead to Industrial Era Romanticism, we have Dvořák’s Romantic Pieces, originally scored for two violins and harmonium. If I thought the previous piece had distinct character changes, I was in for a ride with this one as each piece was a self-contained world of its own, unified only by the shared instrumentation and Dvořák’s compositional style. Consider this a platter of four different appetizers, or wine samples if you will.

The first piece ebbed and flowed delicately with grace and delicate touches from both instruments, treating the return of the theme with a fresh interpretation each time it was restated. We were then thrust into the rustic jollity of a dance-like second piece. Movements of Chalifour’s bow with the many double stops and rapid subdivisions navigated looked almost weightless in motion, but the weight of his attacks constantly reminded me otherwise.

The lyricism of the first piece returned for the third, but with darker undertones throughout, possibly referencing the popular sturm und drang or “storm and stress” style of writing or developing material that preceded the Romantic Era. The fourth piece was a wonderful amalgamation of the preceding characters, almost lamenting in character with every descending statement of the violin as the arpeggiated figures of the piano act almost as musical consolation and response.

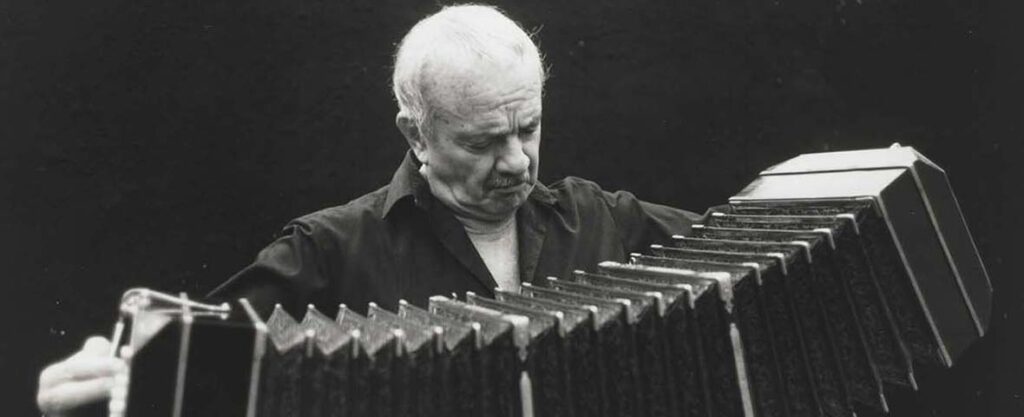

Astor Piazzolla: Histoire du Tango

Designed as a series of tango vignettes from the 20th century, Histoire du Tango is our main course, replete with spice. Influences of Piazzolla’s experience as a bandoneon (type of accordion central to Argentine and Uruguayan tango) player could be felt in the way he wrote, even through this arrangement for violin and piano. Both Chalifour and Vanhauwaert intuitively leaned very tastefully into dissonances, stylistic glissandi, and stressed syncopations.

Considering that this piece was originally scored for flute and guitar, I was amazed at Vanhauwaert’s ease through the extensive and heavy runs in his left hand all while shaping his phrasing with expressive tact. At one point, I thought that someone had percussively erupted into dance within the audience, but quickly saw that Vanhauwaert had also included body percussion on the piano from “Café, 1930” onwards, idiomatic of cajóns and güiros.

Note: Particularly for this piece, I want to stress that the pianist is not merely an “accompanist,” but much rather a dual protagonist. Observing the shift from collectively referring to pianists as “collaborative pianists” in lieu of “accompanists” has been like a cargo ship attempting to turn, but is a much-needed change out of recognition for the heavy lifts pianists do in such chamber settings.

Ralph Vaughan Williams: The Lark Ascending

When I mentioned that this piece was reprised in a more intimate setting than that of when it was performed with a full orchestra at the Hollywood Bowl, I want to be clear that this does not in any way mean sacrificing in body or volume. Quite the opposite. Here comes our second main course.

Though I was seated near the back of the audience, I was still able to hear the delicately articulated chords Vanhauwaert intoned, blended beautifully with the piano’s soft pedal. There was something much more profound about listening to this piece without the amplification it had at the Bowl, and almost being able to see the timbres with which Chalifour and Vanhauwaert wove with ascending to the top of the sanctuary. Only one word continued to linger regarding this piece — tenderness. A melt-in-mouth filet.

César Franck: Sonata in A Major

I feel slight guilt in admitting that I was looking most forward to this piece — Franck’s Sonata in A Major — for a very personal reason: my partner and I have chosen to play the first movement of this piece (arranged for cello and piano) as part of our upcoming wedding ceremony. Everything from the transitive moments of tasteful tonal ambiguity to the beautiful way in which Franck layers all of his musical voices conjures up images of a fine crêpe cake with rich layers of decadent chocolate ganache in between — making for a rather dense dessert to round off the meal.

Franck has a knack for writing with such lyricism and beauty while steering clear from becoming saccharine. His music for keyboardists is, contrary to my food analogy, certainly no cakewalk. Both instrumentalists leaned into their instruments as though to really encourage every note to fully emerge from the sheer intensity and difficult character. The opening theme comes back countless times in different permutations, different tonal centers, different rhythms… yet it still feels fresh all the same. Fervor and frenetically charged passages are balanced well with expansive introversion. Chords were richly articulated in both instruments without harsh crunches, and the piece’s climax was approached with such healthy gravity that the piece’s denouement and final note could be fearlessly approached with equal parts poise and raw enthusiasm.

The Self-Appointed Gourmand’s Review

As verbose as my articles tend to be, these descriptions still do not do these performances the justice they’re due. To quote Marcel Duchamp, “the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualification and thus adds [their] contribution to the creative act.” To get a better sense of the artistry, the synergy, and the energy from both Martin Chalifour and Steven Vanhauwaert, you simply must experience it for yourself!

Both musicians are actively touring, and are regularly in SoCal. Should you find an upcoming concert they will be performing in, I highly recommend checking them out.

This concert was the last of The Music Guild’s 20th Season of SummerFest. An integral presence in the LA area for preserving and advancing the art of chamber music for the last eight decades, The Music Guild plans and presents excellently curated concerts with ensembles experienced and fresh every year for all audiences. For more information on upcoming concerts and ways to contribute to their mission, please visit their website at The Music Guild.

Last but definitely not least, the interviews! Please stay tuned for separate articles with conversations shared with Martin Chalifour and Steven Vanhauwaert coming soon.

Leave a Reply